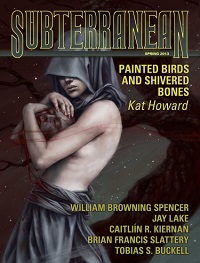

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. In the last installment, I focused briefly on one of the longest-running print magazines, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction; this time, I’d like to return to the world of online publications to note a couple of recent stories that caught my eye. The first, Caitlin R. Kiernan’s “The Prayer of Ninety Cats,” appears Subterranean Magazine, a quarterly publication with a strong track record of publishing quality work by well-known authors. The second is another piece from Jonathan Strahan’s Eclipse Online: “In Metal, In Bone” by An Owomoyela.

I’ve discussed works by both of these writers in the past and I do always look forward to seeing new stories by them—but it’s not only confirmation bias at work in my choice of these two pieces out of the others available in recent publications. These are intense stories, stories that do interesting things with prose and structure; their shared ability to creep under the skin is something that I appreciate.

Kiernan’s “The Prayer of Ninety Cats” has a curious, seductive structure that leads the reader ever deeper into the experience of viewing a film, on a metatextual level and a literal level. The film that the protagonist is watching for review is one layer of story; the actual world outside the film and the protagonist’s experience of it is another. Yet, somehow, it is this fictional film that lingers—the film that I feel, having read this story, I have seen myself. That Kiernan manages evoke this visceral and visual memory in a purely textual story, when giving us the film only in snippets of script and description as the protagonist relays them, is nothing short of stunning. The layer of story about the theater, the often-inexplicable immersion of the artificial screen and what is displayed on it—that layer, for a watcher of movies, is breathtaking in its simple, concise, and real observations about the nature of the medium and the nature of the time spent indulging in it.

The prose, in “The Prayer of Ninety Cats,” is as complex and multifunctional as I have come to expect from Kiernan’s recent work. The imagery is sparse but dense and constantly vivid, spilled in bursts among film script and the protagonist’s internal narration—and it is the combination of these types of prose, the spare and the visual and the internal, that creates the insidious draw of “The Prayer of Ninety Cats.” Kiernan, more generally than this story alone, is concerned with the mechanisms of story, the seduction of narrative, and with externalizing and analyzing those things within other stories, other narratives. The prose here is devoted to this set of fascinating and ever-intense obsessions in the service of film. It’s certainly, as I’ve said, vivid—and also haunting, in the same way that the films it mentions are, those of Murnau, Browning and Dreyer. Creating that effect on the page, without the aid of that screen, earns “The Prayer of Ninety Cats” its top spot in my recent reading.

Though in a quite different vein, Owomoyela’s “In Metal, In Bone” is also concerned with narratives—in this case, the narratives of lives lost and the mechanisms of war. Rather than the creeping embrace of Kiernan’s story, “In Metal, In Bone” hooks the reader into the protagonist’s story hard and fast as he is called to the front of an ongoing, bloody civil war to identify the memories trapped in bones from mass graves. The hard-edged reality that Owomoyela folds into this fantastical plot is enough to stop a reader in their tracks. These are not improbable occurrences, and they are not rendered too awful to believe—the skill, instead, is in painting these atrocities of war as parts of life for many people in the world. The reader cannot place them aside, as something also fantastical. The specific, personal, and intimate detail of the stories provoking and encompassing war—for soldiers, for volunteers from other countries, for citizens—are all present in brief, blinding flashes of honesty.

It’s a subtle story, really, in its effects, where it could be overwrought. This is particularly true of the ending, which is what pushed this piece from merely good to great; the rest of the story, perhaps, could be predicted, though Owomoyela’s execution would remain evocative. The closing, however, where the protagonist is unwillingly drafted from his identification of bones into the army itself—and his reaction to that inevitable inclusion—is understated, soft, and monumental, as is the apology from the Colonel. The detail of the dogtags, their weight of meaning and the potential life-narrative imbued within them, is a strong and provocative image to close on, knowing what we as readers know about the bones the protagonist has been identifying and how.

Both of these stories are, in contemporary parlance, crunchy. They are provocative in their details and their execution, and they linger in the mind in different ways—one as the eerie recollection of a film and the experience of that film, one as a portrait of complex loss, resolution and inevitability. I appreciated both, and continue to look forward to further work from each writer.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.